My Bugout Bag

In this week’s letter, I’m going to walk you through my bugout bag. You’ll hear me refer to this in practice as “running my kit,” meaning I’m emptying out the bag and inventorying the contents. I’ve had the rudiments of a bugout bag for a long time, but I remember running my kit the night after Election Day 2016 as the start of my preparedness journey. Naturally, I ran my kit before the election this year.

You should run your kit once every six months or so, just to make sure your gear is in good shape, you remember where everything is, and that you haven’t let any food or meds expire. You don't want to go for your bag and find out your flashlight died, or that you set the bag down heavy and punctured the seal on your food. You also want to make sure that you swap out seasonal gear, so that you don't wind up with a summer load out in a blizzard.

This is my bag: a Maxpedition Falcon II. I upgraded from a smaller Maxpedition Monsoon that’s still going strong as my wife’s bag. The immediate problem with both is that they (especially mine when packed as above) fairly scream “prepper.” This means that, depending on the situation, any other prepper or someone else on the take will know you’re packing goods that will help them survive—and that’s not a good look. Solid bags can be expensive, so I haven’t made any attempts to replace mine with a more civilian-looking bag, but if you’re just starting out, I recommend you avoid anything with so many bells and whistles as the Falcon II. Maxpedition does have some really decent bags that avoid this look (preppers call it “tacticool”) and will help you blend in while still featuring some things you’ll want. Though, of course, almost any backpack is going to get the job done for you. It just needs to hold stuff.

Pictured here are a military-style canteen with a nesting cup, a paracord bracelet with compass (kept on a strap for ease of access), and a Kershaw Cryo. I keep my EDC kit on my belt, and will add on a large fixed-blade knife if I know I’m running from trouble. The Falcon II has an easy-access pouch at the back that works for concealed-carry, but I’m not there yet.

This is my bushcraft pouch, which I keep on one side of my bag. I can make a simple shelter and start a fire with the contents of this pouch, while maintaining some body heat with the emergency blanket. It’s good to have these materials right at hand because, out of doors, rain and cold will kill you quick. From top to bottom they are: an emergency blanket (you’ll wind up getting several of these by accident when you purchase big first aid kits, survival bags, etc.); some cordage to string up a tarp shelter or whatever (cordage is very useful, and lightweight. Never hurts to have it. Learn some knots now, by the way); a ferrocerium rod which will reliably spark; a plastic tarp; glow stick (mostly just good for digging around your bag or for letting you know where your camp is in the dark); a Procamptek Fatrope Stick, for help starting a fire; and the pouch itself, which was a simple Amazon grab. Your means of starting a fire do not have to be this fancy. Throw some Bic lighters in your bag and soak cotton balls in petroleum jelly and you’ve got an excellent, waterproof firestarter.

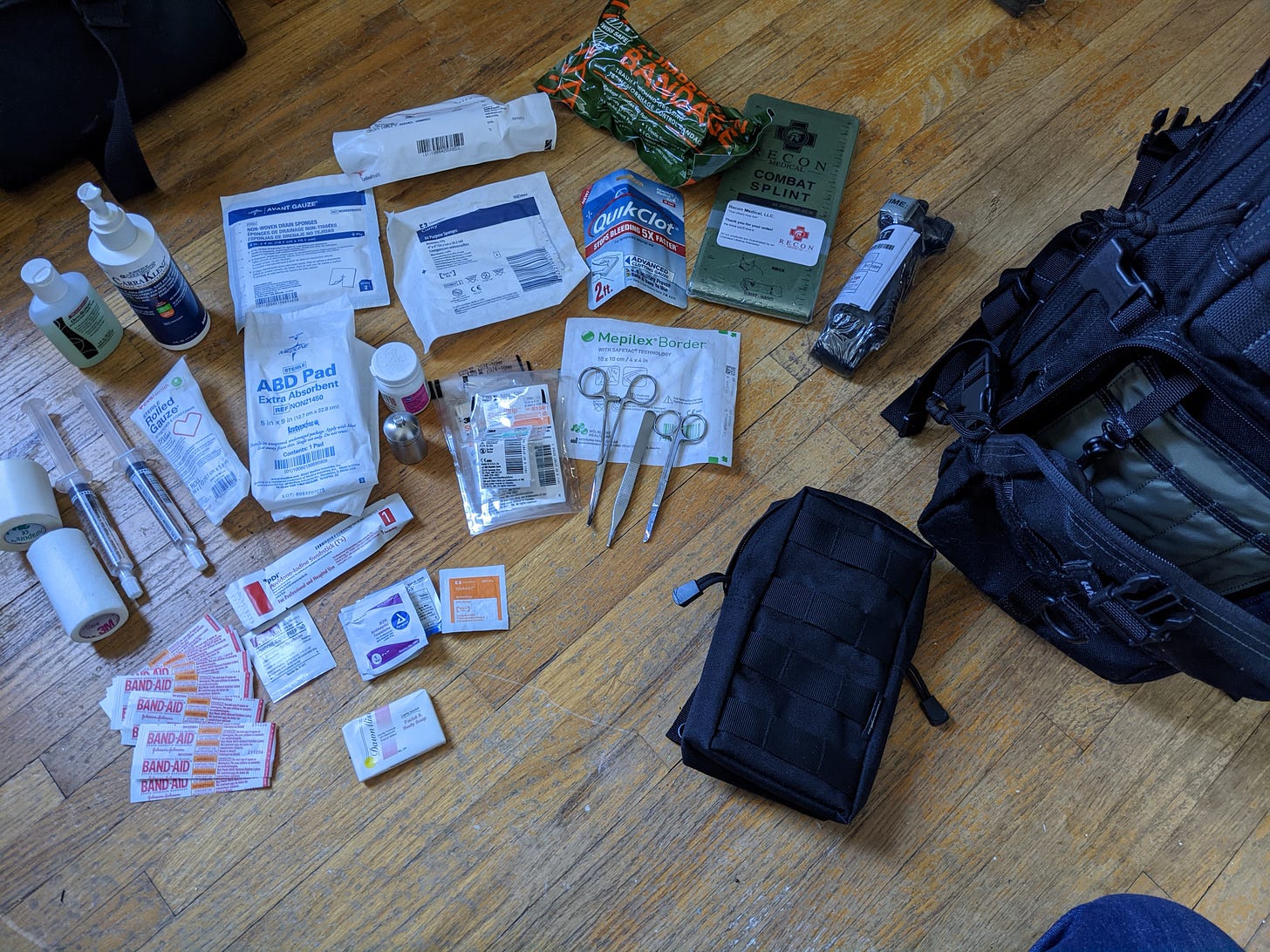

Above are the contents of the first-aid pouch and the pictured open section of my bag. Not pictured is a seal for a sucking chest wound. I’ve got a variety of gauzes, tape, antibiotic bandages, antiseptic wipes, spray, and soap. The syringes are simple saline for wound irrigation and debridement. The pill bottle holds both allergy meds and aspirin, as well as some Pepto chews. The stainless steel container is for additional meds. On the upper right you’ll see QuikClot, a combat compression bandage, combat tourniquet, and splint.

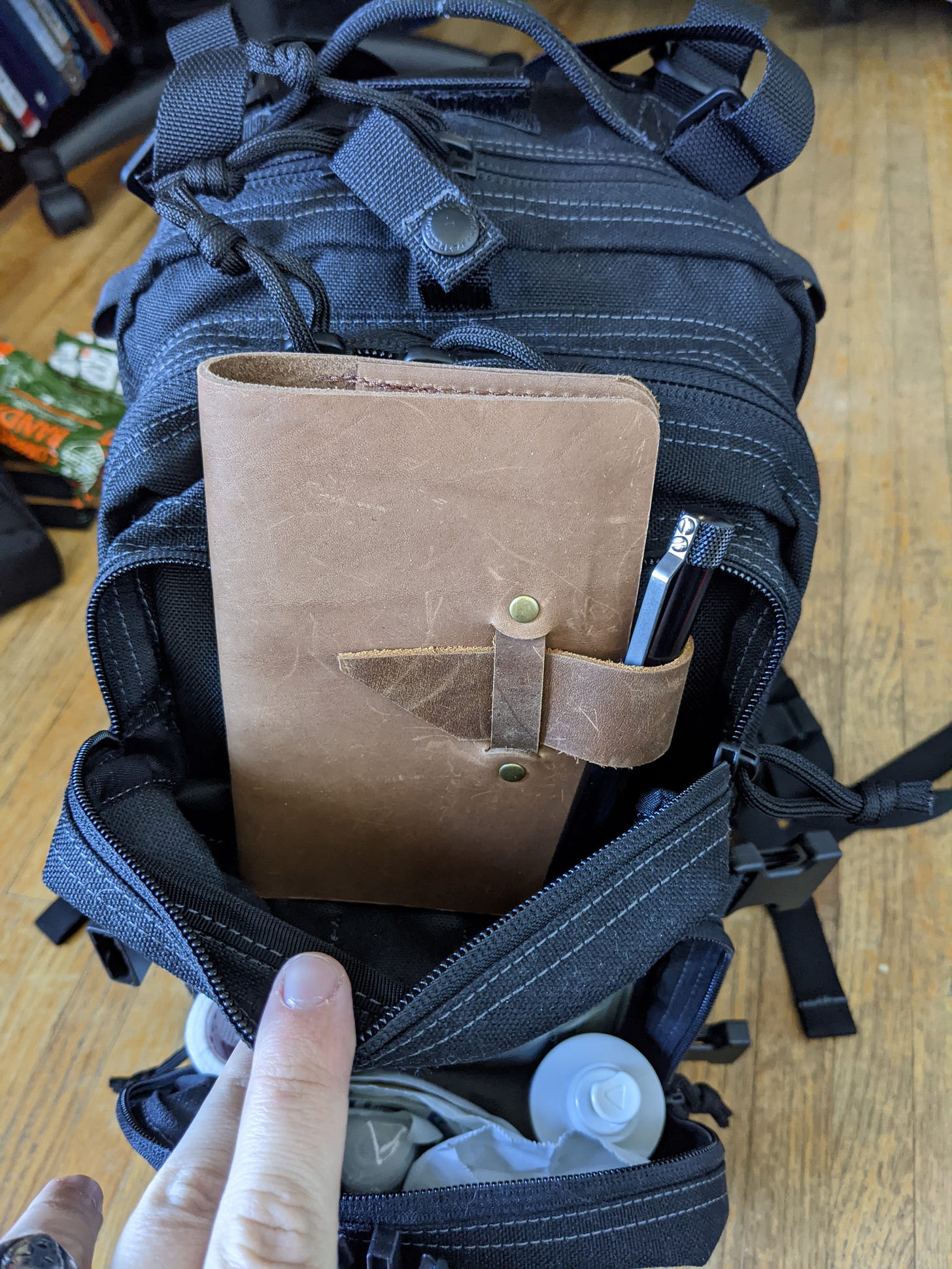

Not every compartment needs to be filled to the brim. This is just a small journal and metal pen. Someday I will add some navigational items to this pouch, which won’t bulk it up much.

The vice compartment! Contains Gorilla tape, a bootknife and sharpener, a Zippo that provides a reliable spark, a little nip of Jim Beam, bath wipes, playing cards (with the plastic wrap still on, and containing $100 emergency cash), and some hot and cold packs. The contents of the burlap sack are below:

Broadheads for use against people or deer, kept in plastic because they are basically razors. On the right are small game arrowheads. I have and intend to bring a takedown bow in the event of a “go into the woods and live your best life” scenario, but this may be less relevant for you.

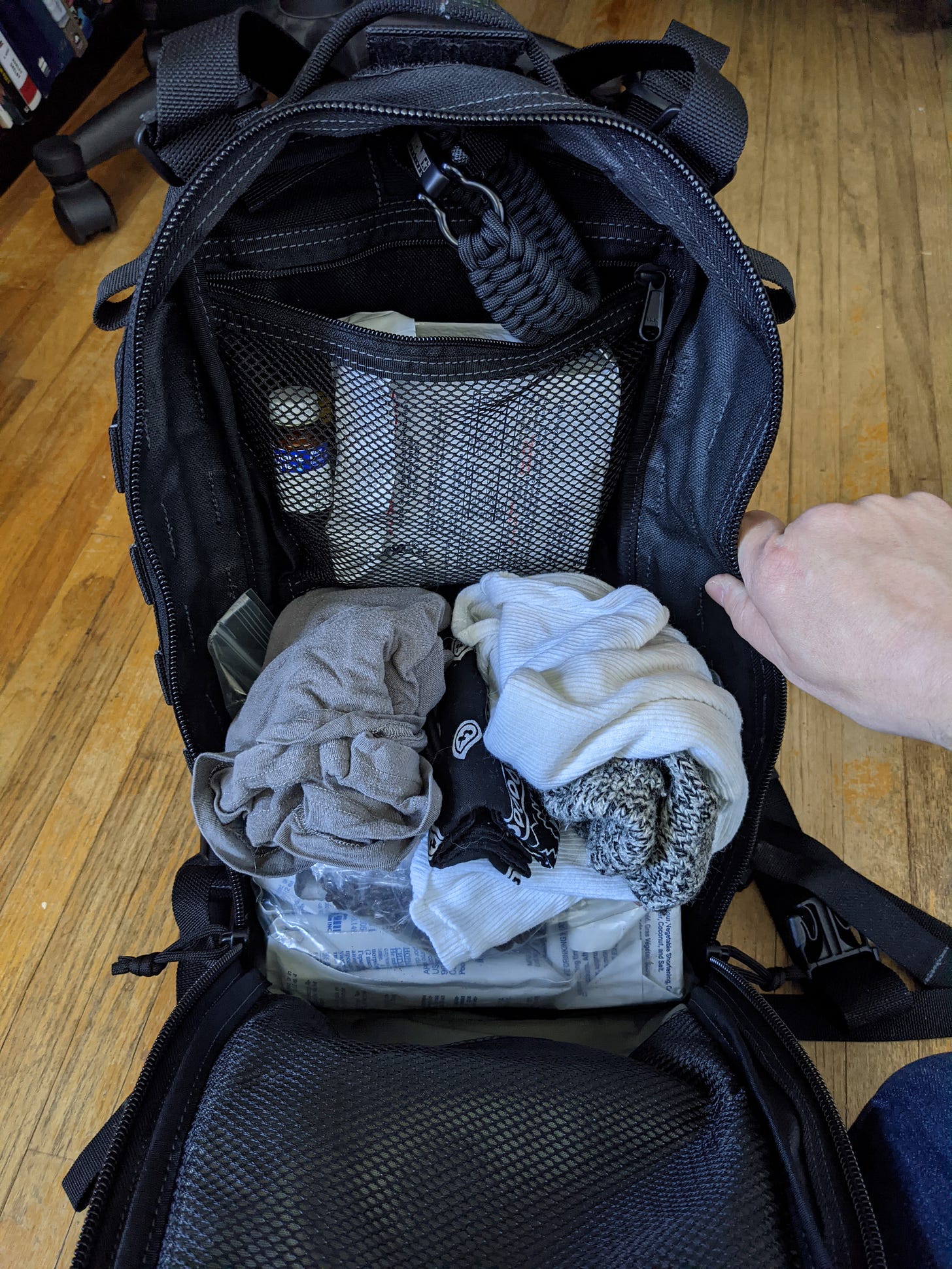

The largest compartment of my bag contains my food, emergency water, and a change of under-clothes. I keep an extra paracord bracelet inside as well. Paracord is a versatile cordage that can be cut to reveal individual filaments, usually consisting of fishing line, a waxed fiber for tinder, a metal wire, and others for a variety of uses or simply as, well, cordage.

My food and water. Not pictured is a Lifestraw and the canteen kept outside my bag. The contents above are a mixture of two survival ration packs (easily more than three days of food, and probably overkill) as well as a broken-down and pilfered MRE. A hot beverage bag and hot meal bag are the long, empty plastics on the right, which combine with the little baggie of ground coffee I have (as well as the coffee crystals from the MRE) to keep my spirits up. (My wife’s bag has tea sachets instead.) Also included are iodine tablets for water purification, in the event that I lose my Lifestraw or it somehow breaks down. Not pictured is an emergency radio and solar lamp (which can hang on the outside of the bag to catch rays).

At the top of the last compartment, I included (post-election) the most important part of my protest kit: a respirator and goggles. This whole bag only runs at about 20.2 lbs, which puts it within the feasible threshold for bugging out without exhausting myself. I should say that this is a pretty thorough loadout, and I could probably bring the weight down to around 18 lbs without missing much. I set up this particular kit, though, with plans to keep it in my vehicle while my wife and I traveled for our wedding (in a ghost town, no worries about social distancing).

The ideal bugout bag is going to weigh somewhere around 15% of your bodyweight, and lower is often better. I’ve got a lot of nifty stuff that you don’t need to replicate precisely, if at all. Your bugout bag should have:

- Water in a good vessel—ideally metal so you can boil more when you run out.

- Emergency rations. If you’re in a pinch, granola or protein bars will do, but good emergency rations will pack more punch for their size and weight.

- A plastic tarp, emergency blanket, and cordage to string a shelter.

- Some method to create fire. My bushcraft gets in the way of my practicality sometimes, but you don't need to bother. A few Bic lighters and some vaseline-soaked cotton balls is fine.

- A first aid kit.

- A compass. I generally go off the tiny ones on my paracord bracelets, but they aren't the best. If you're navigationally challenged, you might want something better.

- A weather radio. I recently upgraded from a small battery-powered model to the linked model that runs off solar and cranks: it's a radio, flashlight, and phone charger in one. I love it.

- A small flashlight (or two).

- A couple good knives. Folding knives are great but you want a full-tang blade as well for heavy-duty work.

- A change of clothes and toiletries. A small bar of soap can do wonders.

Don’t mistake a bugout bag for camping gear. There are a lot of parts in common, but the former is meant for survival while the latter is meant for fun. There are situations in which you might want to bring that tent you got for Christmas, but more likely that's seven pounds of poles and canvas you won't have time to set up on the run.

Partners or friends add good complications to your load out. My wife and I would naturally bug out together, so our bags are designed for us specifically, but in tandem. Some redundancy is necessary (water, food), while others are not (that tent, a bow, folding cookware). Talk to your comrades about what’s in their bags, what they can bring to the table, and, most importantly, where you plan to meet. As with all things, you’ll have a better chance of making it together.

Last thing: I have created a paid subscriber level for the newsletter, but I changed my mind about putting any content behind a paywall. If you’re feeling generous, you can sign up and help me out. If not, you will keep getting updates as usual, and I’ll rest easy knowing I’ve put a little bit of readiness out into the world.